|

| Robert Johnson recorded by Vincent Liebler with production by Don Law (standing) at the Gunter Hotel in San Antonio, Texas in 1936. Artwork by Don Wilson. |

While record producers seem to get all the attention, recognition and glory when it comes to the technical side of music, sound engineers have been mostly relegated to control room obscurity. For instance, many have heard of “The Fifth Beatle” producer George Martin, but few listeners outside of serious Beatles fans or avid music enthusiasts would recognize the names of their engineers Norman Smith and Geoff Emerick. From the start, recording engineers have been key figures behind major technical advancements along with playing indispensable roles in the recording of records. For years I have known that my Great Uncle Vincent Liebler was in the Columbia Records inner circle of engineers who were behind the development of the long playing record, but it wasn’t until 2020 that I became aware of his role in recording Robert Johnson and the extent of his work with Columbia Records. His tenure in the recording industry spanned four decades of technical transformation and musical eras. Further research revealed Vincent was remembered by different people for different reasons. Ardent audiophiles and engineers have helped fill in gaps in the historical record via compelling threads on the Steve Hoffman Music Forums where he is mentioned in almost reverential terms. In other contexts, Vincent is brought up only in passing against the sweeping backdrop history of Columbia Records. Further, an academic-oriented oral history project focused on studio recording led by Dr. Susan Schmidt Horning instigated recollections from his engineering colleagues at Columbia. Part of his obscurity is understandable given Columbia’s size and scope and the fact he rarely shows up in any recording studio photos posted online. When Vincent is mentioned on Wikipedia his name is plain text as there is currently not a biographical entry for him. Although mostly unnoted and unsung, Vincent played an instrumental role in Columbia’s rise to prominence during the mid-century and was involved in three defining moments of historical significance in American music.

For years, Robert Johnson’s groundbreaking songs, recorded in San Antonio (1936) and Dallas (1937), could only be heard through original 78 rpm records issued on the Vocalion label. It wasn’t until 1961, that the music of Robert Johnson was disseminated to a widespread audience via the Columbia LP King of the Delta Blues Singers. These rediscovered songs would go on to not only influence countless subsequent musicians and groups (e.g., Bob Dylan, Cream, the Doors, the Rolling Stones), but would also shift the overall course of folk and popular music in the ‘60s in a more bluesy direction. Columbia Records capitalized on the Robert Johnson resurgence and blues revival and in 1970 issued the second volume of King of the Delta Blues Singers. These two compilations presented the most complete corpus of Robert Johnson’s music at the time (as his entire recorded output is a mere 42 sides). 20 years later, “The Complete Robert Johnson” box set emerged in the CD era and would go on to sell over 50 million copies in the United States alone. The unexpected success of the 1990 box set was partly responsible for sparking the reissue movement at the major label level.

Recording Robert Johnson

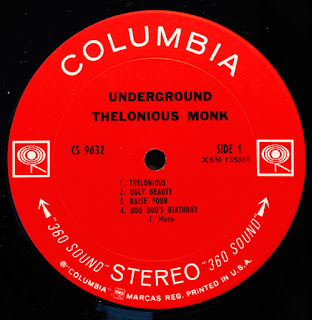

On the back cover of King of the Delta Blues Singers, Vol. II is a Don Wilson illustration depicting two men recording Robert Johnson in an adjoining San Antonio hotel room. The man standing is the legendary Nashville producer Don Law, while the identity of the engineer sitting and recording Robert Johnson has been overlooked. It could also be conjectured that the main engineer on these landmark recordings has also been shrouded in the same speculative shadows that seems to relentlessly loom over so many aspects associated with Robert Johnson’s life, lore and legend. Fact has only recently separated from fiction as more accurate information has recently surfaced on one of the most significant recording sessions in the 20th century.

In the documentation of Robert Johnson, Vincent has generally been unacknowledged or engineering credits have been erroneously given to others such as Art Satherley. However, recent books, especially Up Jumped the Devil: The Real Life of Robert Johnson by Bruce Conforth and Gayle Dean Wardlow have been forthcoming and accurate with the details. The Robert Johnson reissue projects from Columbia Records/Legacy Recordings from 1961, 1970, 1990 and 2011 have also included accurate attributions regarding who was involved with the recording sessions. Being involved in such a monumental moment as recording Robert Johnson should be enough to mark his place in music history, but Vincent went on to change the way we hear and experience music to this day.

|

| 1919 newspaper ad. reflecting the move to Queens and phonograph sales |

Brooklyn Background

Vincent was born on Oct. 6, 1904 in Brooklyn, NY. He grew up in a family that was involved with music on a multitude of levels. His father, George Liebler, worked for a Brooklyn company that manufactured Kring pianos and organs with his father in-law John Schaefer and brother-in-law Edward Schaefer. PH. Kring evolved into a retail piano store which George helped run for 15 or 20 years. The store later moved to Queens where their merchandise expanded to include other musical instruments along with phonographs and records. Kring’s evolution into an overall music store would be a fitting environment to prepare Vincent for his later endeavors. According to the 1920 census, Vincent worked for his father as an "Office Boy." Anticipating his later involvement at the forefront of technology, the 1923-4 Freeport, NY directory listed him as an amateur radio operator. His amateur station 2AVJ operated at 50 watts of power according to U.S. Department of Commerce records. 1923 was the year of radio’s breakthrough with a proliferation of broadcast stations across the land. The public’s embrace of radio sent sales of phonographs and musical instruments into a momentary downward spiral. These early formative working experiences would influence Vincent’s gravitation towards capturing sound. He went on to attend Brooklyn’s Pratt Institute and graduated in 1926 with a degree in electrical engineering. He worked as an electrical inspector for the Long Island Railroad for two years before joining the Brunswick Record Company in 1928 as a recording engineer. Brunswick was the second largest record company during the time. In 1929 & 1930, he was dispatched on field recording assignments in Europe and the Caribbean utilizing portable equipment. Meanwhile, Vincent married Bernadette Theresa DeBus on June 29, 1930 in Northport, New York.

|

| Lieblers in Freeport, NY Jan. 16, 1943 (L to R) Fred, Ed (my grandfather), George Jr., George and Vincent |

Merger City

Brunswick Records was sold off to Warner Brothers Pictures in 1930. Vincent worked for Warner Brothers as a film sound engineer before being appointed assistant chief recording engineer for the American Record Company (ARC) in 1932 after a series of acquisitions and mergers within the entertainment industry. By 1935, he rose to the position of chief engineer for the combined American-Brunswick-Columbia Record Company. In 1936 and 1937, Vincent brought along his previous experience in remote or vernacular field recording to encapsulate the living force of Robert Johnson and record his entire 42-track output. Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) acquired American-Brunswick-Columbia in 1939. That same year, Columbia began operating from the former Brunswick/ Vocalion/ARC building at 799 7th Avenue in Manhattan. This seven floor building, which included administrative offices along with their primary studios, editing, and mastering facilities, would remain Columbia’s long-standing headquarters until fall 1966. CBS’ 1939 acquisition resulted in Vincent’s promotion to Director of Recording Operations for Columbia Records. Besides being chiefly responsible for the overall development of the Columbia studios which also included the intricate technical details, he was involved with a top secret project that would change the world of recorded sound.

History in the Myth Making

It’s somewhat fitting that the only engineer who recorded the King of the Delta Blues be also subject to the misinformation and mythos which permeates the legend and lore of Robert Johnson. Some versions of the story have ARC recording supervisor Art Satherley accompanying A&R producer Don Law to Texas for this remote recording expedition, while other accounts only mention the involvement of Don Law. Recently, the record has been set straight in presenting Vincent Liebler as the recording engineer of the Johnson sessions at San Antonio’s Gunter Hotel in November 1936 and in Dallas in June 1937. San Antonio was a thriving regional recording hub at the time because of its significant Mexican American population along with its relative proximity to the Mexican and Latin American markets. In San Antonio, Don and Vincent recorded Hermanas Barraza & Daniel Palomo and Eva Garza the same week of the initial Johnson “room 414” sessions. From their adjoining control room, Law & Liebler were also able to record some of the country and Western Swing bands that were rollicking in the region including the Chuck Wagon Gang. Six months later in Dallas they continued their recordings of Johnson along with sessions from Crystal Springs Ramblers and the Light Crust Doughboys (former band of Bob Wills) at 508 Park Avenue.

Behind the Scenes

Another way of looking at the origins of the myth making is through the words of John Hammond, an early champion of Robert Johnson and one of the many involved in propagating the mythos. In a 1938 issue of New Masses magazine, Hammond wrote on Johnson: “I knew him only from his Vocalion blues records and from the tall, exciting tales the recording engineers and supervisors used to bring about him from the improvised studios in Dallas and San Antonio.” In a way, Hammond is pointing in the direction of Don Law and Vincent Liebler as fellow co-conspirators in originating the early mythos that would grow to surround Johnson. Still, Hammond was known for his embellishments when it suited him or for the artists who recorded for ARC and Columbia. It has only in the last few years that some details have been substantiated, while conjecture continues to dominate the life and legend of Robert Johnson to the point of becoming a mythical palimpsest of biblical proportions. The rampant speculation and lore has conspired to create more than a cottage industry on its own. Authors Conforth and Wardlow disclosed:

“The only remaining element of the historical Delta that has prospered and grown is the story of Robert Johnson.” (269, Up Jumped the Devil: The Real Life of Robert Johnson, Bruce Conforth and Gayle Dean Wardlow)

A deep well of misinformation and inaccuracies continue to abound in the ongoing search for Robert Johnson that seems to spur the retelling and reimaging of his contested, but captivating story through a book or film about every six months. Vincent could be partly responsible, along with Don Law and Art Satherley for generating some of the early lore that has become indelibly associated with Robert Johnson. Vincent has eventually achieved belated recognition, albeit deep in the margins of music history and somewhat shrouded in the pervasive mystery that has subsumed the influential musician from the Delta.

Facilitating Sound

Recording Robert Johnson was just the start of a long and remarkable career for Vincent. In her book Chasing Sound, Susan Schmidt Horning identified the vast technical proficiencies along with people skills expected and required of successful recording engineers:

“Like the recording artist, the recordist either had it, or didn’t; even experienced recorders might lack what Sooy called “the necessary knack of recording.” That knack involved quick thinking, patience with often temperamental people, and the ability to remain unflappable in the face of trying situations, particularly while on location.” (24, Chasing Sound, Schmidt Horning)

These early recording engineers were required to possess and utilize a wide array of both soft and hard skills while maintaining composure and thinking quickly on their feet. Schmidt Horning’s criteria could be a fitting description for Vincent and his considerable skills as an engineer and rapport with musicians. Furthermore, Schmidt Horning places these mostly unheralded mid-century engineers somewhere between the domains of art and science-bridging the eras of the American Craftsman to the exacting requirements of the electrical engineer: Schmidt Horning further expanded on their versatility: “These men incorporated intuitive knowledge, craft skills, musical sensibility, engineering expertise, and the ability to adapt to unforeseen circumstances.” (8, Chasing Sound, Schmidt Horning)

Engineers have been mostly unacknowledged, but have played indispensable roles in both the art and technical development of recorded sound. It should also be noted that it is common to see the terms of producer and engineer used interchangeably and indiscriminately in music writing without any sort of exactitude or explanation.

Schmidt Horning disclosed, “Although published interviews with recording and engineering professionals date as far back as the 1960s, for at least the first half of the twentieth century, few people outside of the engineering community and the artists and producers who relied on their expertise either knew or cared what recording engineers did.” (7, Chasing Sound, Schmidt Horning)

Recording engineers were challenged to combine the specialized skills of an engineer with the adaptability and diplomacy required to handle strong personalities, in particular the whims and capricious natures of musicians and managers. In the ensuing years, Vincent’s collaborative efforts would help place Columbia Records on the forefront of innovation while also contributing to the overall advancement of technology in the field of audio recording.

|

| Vincent on right with Presto 8DG lathe from the Frederick and Rose Plaut Papers at the Music Library of Yale University |

Inside Track at Columbia

In 1939, Columbia took over the former headquarters of Brunswick/Vocalion/ARC Records at 799 Seventh Ave.at 52nd Street in Manhattan upon Columbia Broadcasting System’s (CBS) acquisition of American-Brunswick-Columbia that same year. During his long career at Columbia Record, Vincent held various titles: Chief Engineer, Director of Recording, Director of Recording Operations and Director of Technical Operations. Whatever the title, Vincent had a significant presence at Columbia Records along with the administrative responsibility of overseeing 84 engineers. In 1948, Columbia broke previously established conventions and introduced the long playing format which revolutionized the world of recorded sound. This breakthrough project was shrouded in secrecy and was said to be 10 years in the works with a hiatus taking place during WWII. Bill Savory, Ike Rodman, Jim Hunter, Bill Bachman, Rene Snepvangers and Vin Liebler were the team of engineers who collaborated to develop the 33 rpm long playing (LP) microgroove record. It has been said the LP wasn’t as much invention as a development. In an article found on the Music in the Mail website: Edward (Ted) Wallerstein, President of Columbia Records from 1939 to 1951, emphasized both the collaborative effort and formative nature of this project:

“From Columbia Records there were Ike Rodman, Jim Hunter, Vin Liebler, and Bill Savory. I had persuaded Bill Bachman to leave General Electric and come to Columbia just before the work had to be stopped. Bill's contribution was tremendous. CBS was represented by Rene Snepvangers, who concentrated on the problem of developing the lightweight pickup that was a key factor in the success of our plans. Peter Goldmark was more or less the supervisor, although he didn't actually do any of the work. I want to emphasize that the project was all a team effort. No one man can be said to have "invented" the LP, which in any case was not, strictly speaking, an invention, but a development. The team of Liebler, Bachman, Savory, Hunter, and Rodman was responsible for it.”

The 12-inch long playing record was unveiled at a June 21, 1948 at a press conference at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in New York City. The timing could not be more apt as its introduction took place on the solstice-that longest day of the year. It would go on to be the day the universe changed in the music industry as the critics were instantly won over by the LP’s length, reduced surface noise and higher fidelity. The format ushered in the now requisite practice of cover art, design and extensive liner notes. These aspects could be arranged to create an immersive audio visual experience. Columbia was able to attract visual artists like the inventor of cover art Alex Steinweiss, Jim Flora, Neil Fujita, Don Hunstein (photography) to visually represent and market the music. Fujita purportedly modified William Golden’s CBS eye logo into the iconic “walking eye” insignia that would go on to emblazon thousands of red labels. This revolutionary advancement in recording technology, which allowed 45 minutes of music, quickly eclipsed the limitations of the brittle 78 rpm record and became the standard format for the listening of recorded music to this day. Sean Wilentz summarized the innovative orientation of Columbia: “The Company has either sponsored or advanced major innovations in sound technology, the most important of which was the invention of the LP.” (10, 360 Sound:The Columbia Records Story, Wilentz) In reaction to Columbia’s breakthrough, RCA placed their efforts and resources into the soon to be equally popular 45 rpm single, which they introduced in 1949. In the ensuing speeds wars, Columbia would become known as the emblematic label of the long playing record.

The Turning Point of the LP

Columbia Records was financially thriving thanks in no small part to a new rising star named Frank Sinatra. Columbia parlayed part of their revenue generated by the kid from Hoboken into research & development. Fittingly, the first full-length pop record released by Columbia would be by the aforementioned Francis Albert. Sinatra would go on to spend the first decade of his career at Columbia. The 12-inch LP format was quickly and enthusiastically embraced by record buyers as it offered a more uninterrupted listening experience at a lower cost. Further, LP record sales were spurred in part by the overall demand for consumer goods in the post-war economy. The LP propelled Columbia’s rapid rise among the leading major labels to the point of direct competition with the mighty RCA Victor.

Production Values

The mid-century saw a remarkable confluence of vastly improved recording technology like magnetic tape and improved microphones coinciding with the breakthrough of the LP and the development and availability of higher quality reproduction equipment. Technical advances like the Ampex Model 200a tape recorder and the Neumann U-47 condenser microphone, both with origins in Germany, enabled the U.S. recording industry to present music with greatly enhanced sonic clarity, depth and wider dynamic range. Magnetic tape and Ampex two-track recorders were also prerequisites in the development of stereo recording which was gearing up in the mid-fifties in preparation for the 1958 market entry of stereo records. Starting in the early 50s, Columbia enthusiastically embarked on marketing phonographs, under the “360 Sound” trade name, manufactured by their parent company CBS and occasionally featuring Garrard turntables. Tonearm adapters and higher quality phonographs were also manufactured by companies such as Philco and Magnavox. These hi-fi sets (and later stereos) became somewhat synonymous with record players in the parlance of the times. According to Sean Wilentz, the late ‘50s saw Columbia offering over 35 phonograph models ranging from portables to furniture consoles all designed to “embody the characteristics of 360 Sound.” (169, 360 Sound Columbia Records Story, Wilentz) Interestingly, it has been said that recording technology during the ‘50s was exceedingly far ahead of the playback equipment of the time. The booming economy also played a significant role in the public’s adoption of the new LP and 45 rpm records. Schmidt Horning chronicled how listeners benefited from advancements in recording technology:

“From the early years of sound recording to the middle of the twentieth century, improvements in recording technology were aimed at the listener, at improving the fidelity of records, with the introduction of professional magnetic tape recorders, improved microphones and high-quality vinyl records." (214, Chasing Sound, Schmidt Horning)

This combination of new technical developments prevailed as industry standards until the digital era. However, the first order of business needed to accelerate the adoption and standardization across competing entities was a formation of a professional organization. Technical standardization proved, for a time, to lift all ships while helping to set the stage to usher in further innovations.

Audio Engineering Society (AES) -The Great Society

For decades there was no professional organization for the commercial audio recording industry partly due to the record companies’ protective emphasis on proprietary. The Audio Engineering Society evolved out of the Sapphire Group which met monthly at the New York Athletic Club in the early ‘40s. The Audio Engineering Society formed in early 1948 and included Vincent and fellow chief engineer colleagues from Mercury, RCA Victor, and Decca along with notables like Les Paul and lathe manufacturer Lawrence Scully as charter members. The AES was also refreshingly inclusive at its inception as it welcomed amateurs-possibly to guard against an being an insular enclave for industry insiders. Annual Audio Fairs which were open to the public and the establishment of a professional journal were among the early accomplishments of the AES. The exchange of technical information and the establishment of industry standards were some of the initial efforts and initiatives which strengthened the emerging field of audio engineering. In the spirit of collegiality, engineers and technicians went beyond the then standard protocols to share the technical details behind their breakthroughs. For example, Vincent demonstrated the long playing record at the September 1948 meeting. By collaborating, the engineers were able to accelerate the advancement of emerging technology which led to the first golden era of high fidelity for audio connoisseurs along with widening the selection of records for the general public in the postwar era. The AES continues to play a prominent role in steering the course of audio technology and shaping the technical side of the music industry to this day.

Susan Schmidt Horning noted the catalyzing effect of the AES:

“By bringing together a dynamic but disparate group of serious amateurs and professionals all concerned with developing the quality and potential of sound recording and reproduction, the AES catalyzed the growth of postwar recording studios and the increase of sound recording and reproduction technologies.” (77, Chasing Sound, Schmidt Horning)

The recording studio would be at the dynamic epicenter where transformative advances in sound recording would take place. Susan Schmidt Horning recognized the new focal points of sound:

“Advances in audio engineering had changed forever the nature of sound recording, of musical performance, and of listener perception of music, and the recording studio was at the center of that transformation.” (139, Chasing Sound, Susan Schmidt Horning)

The end result of this movement are the illuminating recordings where listeners can continue to feel like they are present in the studio with the musicians, producers and engineers, while experiencing part of the transcendent atmospheres cast in these sonic spaces.

|

| "The Church" Columbia's 30th Street Studio (1948-1982) |

Sanctuary of Sound - 30th Street-Columbia Studio

According to Where Have All the Good Times Gone? The Rise and Fall of the Record Industry by Louis Barfem, Liebler and producer Howard Scott frequently scouted out Manhattan real estate for potential new studios and Vincent was the one who first discovered the 30th Street Armenian Orthodox church in 1948. This former liturgical space arguably turned out to be sonically superior to Liederkranz Hall (a German beer hall & ballroom noted to be New York’s leading music studio for years before being transformed into a television studio). Other accounts have Harold Chapman finding the church. Details most likely vary due to mists of time and fallacy of memory. Moreover, the 30th street studio became renowned for its acoustical ambiance and resonance. The cavernous all-wood space allowed a team of sonic craftsmen to utilize its natural acoustics and 47 foot ceiling for state of the art recordings. With baffles they were able to partition and focus the sound within the presence of the large space. The echo, ambiance and sense of openness of the 30th Street studio have yet to be matched and helped facilitate classic recordings like Miles Davis' Kind of Blue and Leonard Bernstein's West Side Story. Susan Schmidt Horning explained it was common in the first half of the 20th century for the major labels to be transient when it came to studios: “Relocation of studios was nothing new, and repurposing existing structures was the way labels set up their recording operations until the 1950s when the Capitol Records Tower in Hollywood became the first purpose-built studios in the American recording industry.” (84, Chasing Sound, Schmidt Horning ) These large foundational efforts coupled with intricate technical details prepared Columbia for the golden age of the recording during the ‘50s.

|

| Interior of Columbia's 30th Street Studio-note the ceiling heights |

Dean of Record Engineers

As a Columbia executive and chief engineer, Vincent was responsible not only to enabling and configuring the technology to consistently reach its fullest potential, but also to innovate in order to anticipate and influence trends in the consumer market. Steve Jobs would later sufficiently encapsulate this consumer psychology concept and capitalist practice as: “Our job is to figure out what they're going to want before they do.” In short, Vincent and the Columbia engineers were shaping the routine and remarkable future. As the ‘40s segued into the ‘50s, Columbia was well positioned ahead of the technical curve which allowed the label to emerge as one of the majors along with RCA Victor, Decca and rapidly rising Capitol Records. He helped establish a culture of exceeding expectations and setting new standards in dynamic sound. Being on the team that realized the accomplishment of the LP, most likely inspired Vincent's visionary practice of placing engineers into roles that demanded more than they thought they were capable of achieving. He wanted his engineering staff of 84 to confront complexity and be capable of taking on formidable challenges. Engineers like Roy Friedman and Frank Laico were placed in positions where they could learn and develop-even if it was going into the unknown and time did not strictly adhere to notions of scientific management or quarterly reports. Work was done with an underlying commitment to presenting the label’s trademark 360 sound with the results emanating from the microgrooves. Its Masterworks label in particular was renowned for its carefully calibrated attention to fine sonic detail as heard on the sweeping recordings by Leonard Bernstein and Andre Kostelanetz. When it came to MOR, Columbia ran circles around their competition. Columbia Records flourished during the recording boom of the ‘50s and was well on its way in becoming a massive international conglomerate.

|

| Vincent's colleagues (L to R): Cal Lampey, Frank Laico bottom row: George Avakian, Roy Friedman |

By the mid-fifties, Vincent was known as the “Dean of Record Engineers” by his colleagues and one of few remaining employees left from a previous sepia-toned age where Columbia Records had only a dozen employees. He not only recognized and hired emerging young talented engineers like John McClure (classical) and the aforementioned Frank Laico (who would go on to record landmark achievements by Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, Dave Brubeck, Frank Sinatra), but also placed them in recording and editing situations to learn, adapt and develop in the studio. Along with Howard Scott, he supervised Cal Lampey from 1949 to 1954 who worked as a music/tape editor at Masterworks. Cal Lampey later went on to produce such musicians Miles Davis, Pucho & The Latin Soul Brothers and Freddie McCoy. Schmidt Horning credits the culture of mentorship combined with a hierarchical infrastructure of the time as instrumental in presenting an identifiable and cleanly articulated sound.

Schmidt Horning noted, “The major label studios based in New York and Los Angeles maintained high standards consistent with their technological capabilities, training young engineers for months and even years to maintain consistency in the company’s particular sound.“ (139, Chasing Sound, Schmidt Horning)

Vincent’s colleague George Avakian was able to lead Columbia’s jazz division to the realms of the elite independents like Clef/Verve Prestige, Riverside and Blue Note, before departing in 1958 for World Pacific and later Warner Brothers Records. The longer length enabled by the LP’s “microgroove technology” perfectly suited the presentation of jazz music. The hits of the pop division (enter Johnny Mathis, Tony Bennett) were able to subsidize their Masterworks classical efforts, while jazz recordings like “Kind of Blue” by Miles Davis, “Time Out” by Dave Brubeck and Erroll Garner’s “Concert by the Sea” crossed over to commercial mainstream success. Further, perennial thrift store album filler and finery from Ray Conniff, Mitch Miller and Broadway cast albums (e.g., West Side Story, My Fair Lady, Flower Drum Song and South Pacific) helped propel Columbia to finally supplant RCA Victor and ascend to the top of the record industry by the end of the ‘50s.

Vincent’s continual efforts gave the label consistency and continuity as his working career spanned several eras of Columbia Records and the recording industry. In addition, he further augmented Columbia’s reputation for first-rate sound quality and artistic achievement by mentoring and elevating those around him. At the mid-century mark, the highly capable engineering division helped Columbia Records reach new heights along with positioning the label to be a leading technological innovator in the recording industry for decades to come.

The Columbia 360 Sound

Columbia became renowned, in part, due to their astute attention to sonic detail and depth and in the process becoming the standard-bearer in the music industry as the label became synonymous with high fidelity:

“Columbia Records mean class and quality-New York style. The recording, mixing, mastering, pressing-the whole lot-were never less than the standards of the day." (185, Temples of Sound, Jim Cogan and William Clark)

It was during the whirlwind ‘50s that Columbia established itself as a cultural icon that continues into this century. While Columbia already had a simple bold and strong visual identity thanks in part to the art direction of the aforementioned Neil Fujita, Vincent and colleagues helped establish their signature sound. “You always used to know the sound of a Columbia record because of the sound,” proclaimed Bruce Botnick. (49, Temples of Sound, Cogan and Clark)

|

| "Walking Notes" & 360 Sound Label shot courtesy of LondonJazzCollector |

Columbia was able to put the sound in perfect alignment to express an expansive and spacious 360 sound:

“Working in conjunction with its then owner, the Columbia Broadcasting System, Columbia coined the slogan “360 Sound” in the early 1950s in order to help market its efforts in so-called “high-fidelity” recordings. Between 1962 and 1970, “360 Sound” appeared on Columbia’s record labels, bracketed by two arrows, which quickly became one of the company’s better-known trade emblems.” (13, 360 Sound:The Columbia Records Story, Wilentz)

Historian Sean Willetz eloquently encapsulated these iconic years:

“Over the decade and a half after the war’s conclusion, the label acquired a new cosmopolitan prestige, a reputation for technical virtuosity, and a carefully cultivated image of refined exuberance.” (123, 360 Sound: The Columbia Records Story-Wilentz)

Taking Transatlantic Flight

The label expanded out in new sonic realms in the scientific age. During the post-war period, Columbia had grand and adventurous plans that mirrored the acceleration of the jet age, the space race and increased prosperity for some levels of society. Gary Marmortein observed, “The LP also arrived in a postwar period in which Europe was more familiar than ever to Americans. Airlines like TWA and Pan Am scheduled more flights to Paris, London, and Rome,” (231, The Label, Marmorstein). In addition, LPs were easier to import and export as the lighter weight and increased durability made them more viable and lucrative to transport via air.

National Breakout

While studios and their corresponding letter designations get thrown around casually and often inaccurately in recollections by both critics and musicians, the study of the individual studios, especially the ones in New York, can also be byzantine. In the late 40s, the majors of the record industry were entrenched in the Northeast with headquarters in Manhattan and manufacturing facilities operating out of Connecticut and New Jersey. Columbia Records conducted business and recording (Studio A) from a seven-story building at 799 Seventh Ave. since the late ‘30s. As the nation’s population began its shift to the West, it was time for Columbia to widen in scope both geographically and musically. Vincent became responsible for overseeing the acoustic design, renovation and construction of the recording studios. To put it in more streamlined terms, he became an acoustic architect. By the mid-fifties, Vincent was overseeing the design and construction of Columbia’s studios. He collaborated with colleagues to help design studios which captured some of the most remarkable musical performances which have not only stood the test of time, but also stand as summits in recorded sound. Besides the population shifts, stereo recording spurred the upgrade of existing studios and the impetus to build new studios. In Columbia’s case, both the 30th Street and the 799 Seventh Avenue in New York were modified and expanded to accommodate stereo recording.

Vincent was not only responsible for technical matters at the New York epicenter, he also assisted Columbia with their grand expansion across the country during the late ‘50s & early ‘60s. Columbia subsequently established and expanded dedicated state-of-the-art recording facilities in the music industry cities of Nashville, Chicago and Hollywood. The Chicago and Hollywood sites both required modifying the pre-existing radio station studios (WBBM in Chicago) and (KNX in Hollywood) owned by CBS Inc. In Nashville, Columbia bought Owen Bradley’s legendary Quonset Hut on music row prior to his 1962 move out to Bradley’s Barn in Mt. Juliet, TN. Vincent’s old “roving” recording colleague Don Law, who was Columbia’s top producer in Nashville, convinced the label to purchase the Bradley’s Quonset Hut and establish Columbia presence on music row. (Bob Johnston would succeed Don Law upon his retirement in 1967 and go on to produce the Byrds, Johnny Cash and Bob Dylan in the Music City.) By gaining a presence in the South and also West of the Rocky Mountains, Columbia was now oriented towards the entire country. Working in unknown territories, Vincent helped disseminate the consistent and consonant Columbia sound across the land. In addition to the Westward expansion, Columbia was also well on its way to becoming a massive international conglomerate with offices and recording studios from Toronto to Tokyo. Adding and expanding recording facilities in Nashville, Chicago and Los Angeles prepared Columbia for what was to arguably be the most momentous decade of American music and culture. As Director of Technical Operations, Vincent helped lay the foundation for engineers to capture the new groundbreaking sounds that would go on to leave an indelible mark on American music.

|

| Vincent co-coordinated the Nashville studio enlargement project with Michael N. Salgo, CBS engineer |

Unexpected Turns

The fifties would see a new rising star emerge from the West Coast. From the epicenter of Hollywood, the Capitol Records tower, both symbolically and physically rose above all others upon its completion in 1956. Admittedly, when it came to major labels, Capitol has been my long time favorite for the fact of releasing unsurpassed recordings from the Beach Boys, the Beatles, Frank Sinatra and Buck Owens & the Buckaroos not to mention their striking swirling orange/yellow label design. When I was a kid Columbia, meant heavily promoted releases from Bruce Springsteen and Billy Joel and little did I know that Epic was a Columbia subsidiary-let alone their affiliated labels Date and OKeh. Unlike Capitol, Columbia seemed not to be really a label that would look that cool on a t-shirt. Accordingly, the Capitol Records tower was my first stop upon my initial visit to Hollywood.

|

| Music Reporter-March 7, 1964 |

Hollywood Happening

In Spring 1961, Columbia’s first recording studio on the West Coast opened at 6121 Sunset Boulevard between Gower Street and El Centro Avenue in Hollywood. It was located in the epicenter of the Hollywood music scene as the Hollywood Palladium, Wallich’s Music Center, and RCA Victor’s Music Center of the World were right down the Sunset strip to the west. Mitch Miller and Vincent hired Allan Emig from Capitol Records as Director of Columbia’s West Coast Recording Operations. According to Susan Schmidt Horning, Columbia’s new West Coast Facility was the former CBS Radio Studio A in the KNX building on Sunset Boulevard. The radio studio was immense as it was built in the pre-TV era when stations would accommodate large studio audiences. The radio studio was one of three International Style buildings designed by William Lescaze, which comprised the CBS Columbia Square complex which was originally completed in 1938. The modification of the expansive radio studio space, with forty foot ceilings, cemented and symbolized Columbia’s commitment to the West as the label previously limited itself to rented studio space. It opened as the largest single recording studio on the West Coast and was even known as "The Basketball Court." As with the hallowed 30th Street studio in New York, the immensity of Studio A was partitioned with sound direction baffles. Vincent conveyed the engineers’ excitement to work in this sleek and streamlined studio:

“Columbia engineers are particularly enthusiastic about the reverberation characteristics of the new studio and consider them revolutionary in the design and construction of recording studios,” wrote Vincent Liebler in The Columbia Record for April/May 1960.

Susan Schmidt Horning elaborated on the increasing importance of engineers to design studios that could quickly adapt to the accelerated popular culture of the ‘60s which emanated from the West Coast and would subsequently sweep across the country:

“Moreover, because styles of popular music changed over time, flexibility was now considered important in studio design. Recognition that the recording studio was now a critical factor in a record’s success meant that acoustical engineers became increasingly important to their design, but even they recognized the bottom line as the buying public." (88, Chasing Sound, Schmidt Horning)

In 1963, Columbia opened a pressing plant and warehouse in Santa Maria, California. With operations on the West Coast, Columbia now had the three major regions of the country covered with manufacturing/shipping facilities. Columbia ran three major plants for vinyl pressing along with distribution centers in Terre Haute, IN (1953-1982), Pitman, NJ (1960-1986) and Santa Maria, CA (1963-1981). 1955 saw the launch of the instantly successful Columbia Record Club (later Columbia House) in which the increased durability and portability of the LP made them viable for mailing. According to Gary Marmorstein, “Columbia chose Terre Haute, Indiana, where LPs were already being pressed, because the Midwestern location facilitated shipping to all parts of the country.” (222, The Label, Marmorstein) In 1970, president of Columbia Records Clive Davis opened a Columbia Records studio in San Francisco to cater to his acts like Big Brother and the Holding Company and Sly and the Family Stone.

|

| CBS Columbia Square-6121 Sunset Boulevard at Gower Street in Hollywood, CA |

CBS Columbia Square The sizable studio at CBS Columbia Square reflected the spacious and wide sounds to be encapsulated inside. With a control room large enough to accommodate both the engineer and producer, the Columbia Studios complex was now in perfect alignment for the breakthrough of the Byrds and other West Coast acts with newly attuned sensibilities. During the early sixties, Columbia was the consummate middle of the road label, but music and society were rapidly veering away from the center. With the analog age at its zenith and technical framework established, Columbia had to quickly catch up with the musical content in the pop-art age. Gary Marmorstein elaborated, “Musically, Columbia frequently found itself flat on its back clueless, left behind, But part of its strength was its ability to pick itself up, dust itself off, and readjust according to the times.” (xiii The Label, Marmorstein) While Columbia seemed to be languishing for a time when it came to rock ‘n’ roll (outside of a brief burst of burning rubber with the Rip Chords), they quickly made up for the lag time via a chain of mostly unforeseen events. Through the influential Miles Davis, the Byrds were brought to Columbia where they auditioned for producer Terry Melcher. Wunderkind Terry was brought in to quickly get Columbia Hollywood up to '60s youthquake speed. Melcher remarked on the lack of street credibility he was up against when he started to make a name for himself -besides being the only child of Doris Day.

“Apart from the Rip Chords, Columbia had absolutely no teen music credibility in Los Angeles at all. Neither did Capitol, RCA didn’t much, aside from Elvis Presley-at that point recording “Do the Clam.” So the majors were experiencing a dearth in the whole teen music thing. Little indie labels were enjoying a lot of success-everybody wanted to be at Liberty Records and companies like that.” (Terry Melcher, The Best of Bruce & Terry liner notes, Sundazed Records)

Terry’s musical partner, Bruce Johnson, chimed in: “Remember, the big albums of the day were South Pacific, Johnny Mathis albums-they were the multi-platinum albums of that time. And all the really cool music was mostly on independent labels.” (Bruce Johnston,The Best of Bruce & Terry liner notes, Sundazed Records)

|

| Billboard Magazine-Jan. 23, 1961 "The over-all project is under the supervision of Vincent J. Liebler" |

Full Flight While Columbia got a late start in rock ‘n’ roll, partly due to shielding themselves from the sordid world of payola, they quickly made up for it with some of the most distinctive, enduring and influential groups of the ‘60s. With Dylan, Simon & Garfunkel and the Byrds on their roster, Columbia was on the vanguard of folk-rock which meant the forefront of rock ‘n’ roll at the time. Their first two albums, produced by the aforementioned Terry Melcher, would go on to open wide the folk-rock floodgates in 1965, while ushering in a new era at Columbia Recording Studios. Author Ianthe McGuinn was present at many of the Byrds recording sessions both at intimate World Pacific in Los Angeles and Columbia in Hollywood. "I walked into a cavernous, well-lit room, large enough for an orchestra," wrote McGuinn. "It was magical to hear their harmonies blend, the studio's huge speakers and audio gear filled the engineer booth with overwhelming sounds." (48-49, In The Wings, McGuinn) Columbia also did not spare any costs with frequent studio appearances by legendary session musicians like Glen Campbell, Leon Russell, Hal Blaine and Earl Palmer and the rest of the Wrecking Crew. The Rip-Chords, Chad & Jeremy, Paul Revere and the Raiders, Buffalo Springfield, the Chambers Brothers, the Peanut Butter Conspiracy and Moby Grape all recorded at Columbia Recording Studios on Sunset in Hollywood. In addition, the studio sunshine pop of Sagittarius (Gary Usher, Curt Boettcher, Keith Olsen) first rose from the Columbia studio. Even Brian Wilson recorded portions of “Good Vibrations” at Columbia because it was the only studio equipped with an 8-track recorder at the time. Brian Wilson led the movement to utilizing multiple studios and in doing so elevated pop music to a summit during this transformative time. The 8-track recorder allowed for more versatility and played an indispensable technical role in multitrack recording.

Susan Schmidt Horning revealed:

“The Beach Boys became the first major rock group to go outside their label’s in-house studio when Brian Wilson chose to use a number of other Los Angeles area studios, including Western, Gold Star Wally Heider and Sunset Sounds, as well as Capitol, Columbia, and RCA, to record various parts of songs.” (200, Chasing Sound, Schmidt Horning).

This shift away from Capitol’s in-house studio offered more flexibility along with expanding the opportunities for Brian Wilson to produce his own records. In contrast, the Byrds first recorded their staggering “Eight Miles High” at RCA, only to be rejected by Columbia Records as it was not recorded at Columbia Recording Studios.

|

| The Byrds recording at Columbia Recording Studios in Hollywood |

Engineering Excellence

It has only been in the 21st century that the studio/session musicians such as the Wrecking Crew and the Funk Brothers have been recognized for their vast contributions in the creation of some of the most timeless and enduring pop music ever released. On a similar note, Susan Schmidt Horning calls for engineers to be credited for their unsung efforts:

“While recording stars and record producers enjoyed public recognition, recording engineers often contributed far more to recording than they received credit for doing, as did session musicians whose playing on some records was attributed to others.” (212, Chasing Sound, Schmidt Horning)

Paralleling the acknowledgement received by the previously unheralded studio musicians, engineers like Dave Hassinger are finally being given belated credit for their efforts here in the 21st century. In Hassinger's case, he was the chief engineer of the peak-era Rolling Stones (‘64-’66) and for a majority of the Electric Prunes recordings. The overdue acclaim for engineers might be partly due to the fact disclosed by Schmidt Horning: “Engineering credits on record albums didn’t become common until the 1960s” (101, Chasing Sound, Schmidt Horning). While considerable progress has been made in recognizing the importance and contributions of audio engineers, they continue to remain mostly overshadowed despite their specialized knowledge and integral abilities which makes the recording process and listening experience possible.

It was fitting that in the final stretch of his career Vincent appeared in a 1966 advertisement for the world-renowned U67 condenser microphone designed by Georg Neumann and introduced in 1960. These high-caliber microphones were distributed by the German electronics giant Telefunken and were the successor to the U47 (which was known as a vocal microphone and was championed by Frank Sinatra). To this day, the U67 is mentioned with reverential tones by the recording professionals due its versatile ability to capture a variety of vocal and instrument tones with unmatched sound quality.

Continuously evolving?

The gear race and the movement to independent studios followed in the late ‘60s and contrasted the mid-sixties practice of recording at in-house record labels where it was common for the label engineers to build the sound recording equipment and studio control consoles themselves. These label engineers helped set the stage to consistently record some of the most cohesive and extraordinary pop rock music of the mid-1960s. Schmidt Horning identified the newly crowded field of pro audio during the late ‘60s:

"The growth of professional audio products manufacturers escalated, introducing new, improved versions and different gadgets, assuming a kind of technological momentum that seemed inevitable, full of potential for creative uses, and thus technology could be used to influence the cultural product. (216 Chasing Sound, Schmidt Horning)

Vincent worked all the way through to the dawn of psychedelia, the great gear race, the expansion into multi-track recording and the studio-as-instrument. A November 18, 1967 Billboard article by Claude Hall titled “Record Companies Bust Out In Coastwide Studio Spree” presents the fledgling studio scene that was soon to reach a crossroads. It starts with declaring that 1967 will be known as “The year of the studios” with a surge in new construction and remodeling because of two factors: "Rock ‘n’ roll groups need more studio time in their quest for new sounds and engineers have advanced technology to such a high degree that complicated equipment and controls are necessary." The article goes on to mention the openings of the A&M studios on LaBrea in Los Angeles and John Fry’s Ardent Studios which had the distinction of being the first 8-track studio in Memphis. The article concludes with the following quote by Vincent: “At one time, we did everything in monaural. Then came three-channel and four-channel. Now, if you don’t have eight-channel equipment, you’re a nobody.” Vincent was able to experience the last heyday of the major label studios when the practice and excitement of recording live in the studio still existed. After only a decade, the halcyon days for Columbia Records studios in Los Angeles ended in 1972. The closure was precipitated by the trend towards independent studios, producers and engineers. The more relaxed and intimate recording atmospheres found at the independents like Sunset Sound, United Western Recorders, Cherokee, Valentine, instantly enticed musicians. While these lavish sonic spaces perfectly suited the '70s, they surrendered some of extemporaneous live energy and momentum in the multi-tracking and post-production process. Schmidt Horning indicated the shifts in priorities:

“Unlike the days of Liederkranz Hall, the ambience of a studio no longer meant its acoustical perfection, rather it was the “vibe” given off by those who worked there, the “feel” of the surroundings, an exotic or secluded location, hip interior design, amenities such as hot tubs and sleeping accommodations, and access to all kinds of indulgences.” (209, Chasing Sound,Schmidt Horning)

Vincent’s career closely coincided with Columbia’s ascent to the top. 1965 and ‘66 were Columbia's best years to date. One of Vincent's last major projects in fall 1966 was assisting Columbia Records move from its longtime home at 799 Seventh Ave to 49 East 52nd Street where recording sessions resumed in studios B and E. CBS corporate regulations forced mandatory retirement at age 65. Fittingly, Vincent retired in 1969 right before the bloated era of corporate excess in the music industry. He died on Oct. 26, 1989 at Medical Center of Vermont in Burlington. He was buried at St. Philip Neri Cemetery, East Northport, Suffolk County, New York.

|

| The Columbia Recording Studios at 49 East 52 St. opens Cash Box-Dec. 3, 1966-Vincent on right with Leroy Friedman in middle |

Bridging the Technological Eras

Throughout his remarkable career filled with moments of historical significance, minor revelations and major accomplishments, Vincent regularly did what was deemed difficult or not thought possible at the time. He seemed to be on the forefront of technology while also being a bridge figure providing continuity from one era to the next. Over a career spanning four decades in the music industry, Vincent was a leading light who helped change the trajectory of Columbia Records and recorded music. First, he was part of the collaborative effort that helped develop the long playing phonograph record. Second, Vincent played a multifaceted role at Columbia with establishing the technical foundation to help Columbia operate state-of-the-art recording studios in New York, Chicago, Nashville and Hollywood. In short, he played a major part in the design and construction of these temples of recorded sound across this land. These accomplishments demonstrated that Vincent was adept at placing the composite parts into an unified whole. Lastly, he captured one of the most defining moments in history of American music when he recorded Robert Johnson’s scant, but monumental and influential output. The impact these 1936-7 sessions would have on future musicians, writers, filmmakers and researchers would not be seen, heard and felt until decades later.

His engineering efforts and administrative leadership at Columbia helped spur the advance of technology and brought things to fruition. In other words, he seemed to be the rare breed of a visionary who got things done. As a key figure at Columbia Records for decades, he was a consummate engineer in the shirt and tie era. At Columbia, he demonstrated his versatility in transitioning through several musical eras while exemplifying fortitude and patience in dealing with the strong personalities of musicians and mercurial presidents like Edward Wallerstein, Goddard Lieberson and Clive Davis. Overall, he helped Columbia vault into national prominence with his efforts to make exceptional sound the label’s mark of distinction.

The relatively unheralded engineer could be said to be an American Tonmeister who played an instrumental part, working behind the scenes, in the history and evolution of recorded music. The development of the LP was monumental for both the record industry and popular culture-profoundly changing the way music is listened to and still influencing the form and function of our contemporary culture. He acted as both a catalyst and a collaborator in converging technology and music together into a preeminent and enduring sound. By arranging space and optimizing technology, he played an integral role in the advancement of studios which allowed the recording of sound to reach soaring new heights. Above all, he helped reshape sound forever while also recording music for the ages.

|

| Vincent in Terre Haute, Indiana with my Grandfather & Grandmother |

Acknowledgments

Special mention and thanks to my sister Jill who encouraged me to explore family history and did the in-depth genealogical research on the Liebler family in New York during the first half of the 20th century.

Thank you to Ianthe McGuinn for permission to quote her regarding her recollections of the Byrds recording at Columbia in Hollywood.

Barfe, Louis. (2013). Where Have All the Good Times Gone? London: Atlantic Press.

Cogan, Jim., & Clark, William. (2003). Temples of Sound: Inside the Great Recording studios. San Francisco: Chronicle Books.

Conforth, Bruce (2019). Up Jumped the Devil: The Real Life of Robert Johnson. Chicago: Chicago Review Press.

History of CBS RECORDS 30th Street STUDIO NYC (many pictures). (n.d.). Retrieved February 23, 2021, from https://forums.stevehoffman.tv/threads/history-of-cbs-records-30th-street-studio-nyc-many-pictures.388186/

Hjort, Christopher (2008). So You Want to Be a Rock 'n' Roll Star: The Byrds Day-By-Day 1965-1973. London: Jawbone Press. Horning, Susan Schmidt. (2015). Chasing sound: Technology, Culture, and the Art of Studio Recording from Edison to the LP. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Jenkins, A. (2019, April 13). Inside the Archival Box: The First Long-Playing Disc. Retrieved January 13, 2021, from https://blogs.loc.gov/now-see-hear/2019/04/inside-the-archival-box-the-first-long-playing-disc/

LondonJazzCollector (n.d.) Retrieved February 16, 2021, https://londonjazzcollector.wordpress.com/

Marmorstein, Gary. (2007). The Label: The Story of Columbia Records. New York: Thunder's Mouth Press.

McGuinn, Ianthe. (2017). In the wings: My life with Roger McGuinn and the Byrds. Worksop, Nottinghamshire: New Haven Publishing.

Priore, Domenic. (2007). Riot on Sunset Strip: Rock'n'Roll's Last Stand in Hollywood. London: Jawbone Press.

Unterberger, Richie. (2002). Turn! Turn! Turn!: The '60s Folk-Rock Revolution. San Francisco: Backbeat Books.

Wilentz, Sean. (2012). 360 sound: The Columbia Records Story. San Francisco, Calif: Chronicle Books.

WorldRadioHistory.com (n.d.). Retrieved January 31, 2021, from https://worldradiohistory.com/

Thank you for this awesome insight. Interesting to see Vincent pictured with the Presto 8DG lathe which would be around 1949-50 at the earliest iirc. Curious if he had a history or even preference for using Presto lathes? They were one of few making portable units in the mid 1930s with the model 16x.

ReplyDeleteI appreciate you reading and commenting. Your eye for detail brings a new consideration to the table. In my incomplete research, I did not come across Vincent's technical preferences beyond his ad endorsement for Neumann condenser mics. If anywhere, possible clues might be found in the AES Journals that I don't have access to.

ReplyDelete